Adapted from an email series sent by https://moretothat.com.

At first glance, this might sound like a ridiculous question. After all, who doesn’t know what a story is? But if you actually sit with the question for a moment, you’ll realize that the answer isn’t so obvious.

What differentiates a story from a series of statements? Why do some conversations feel like you’re exchanging stories, whereas others feel like you’re simply exchanging words? Why do some books feel like you’re part of a narrative, whereas others feel like a mere transmittal of information?

These questions are especially pertinent in the domain of nonfiction. With fiction, it’s implied in the medium that you’re going to make use of your imagination. But with nonfiction, it’s different. You’re expecting to learn more about the structure of reality, so you may not be expecting narrative arcs, characters, and devices of this sort.

And herein lies the great secret: Storytelling is an immensely underrated skill, especially in nonfiction.

Nonfiction creators often don’t think of themselves as storytellers. We often think of ourselves as idea distributors, where we share what we know so we can contribute to the ever-growing body of human knowledge. While this is fine, it’s not enough if you want your ideas to spread.

With that said, we can now arrive at my definition of a story:

That’s it. It sounds simple, but trust me, that single sentence will require a ton of unpacking.

Web of Ideas

How do you know which ideas will form the foundation for your story? Where do you even begin? We live in a vast universe of ideas. There’s no shortage of inspiration or insight available to us, as everything we want to know is just one search away.

The problem with this abundance, however, is that there’s too much to sort through. When we’re looking for the ideas that will become our stories, how do we know where to start? Which ideas have the potential to become a story?

Well, I have a solution to this conundrum. It turns out that every idea you’ve come across has a story embedded in it. But to unearth it, you need to use this wonderful tool: The Thematic Lens.

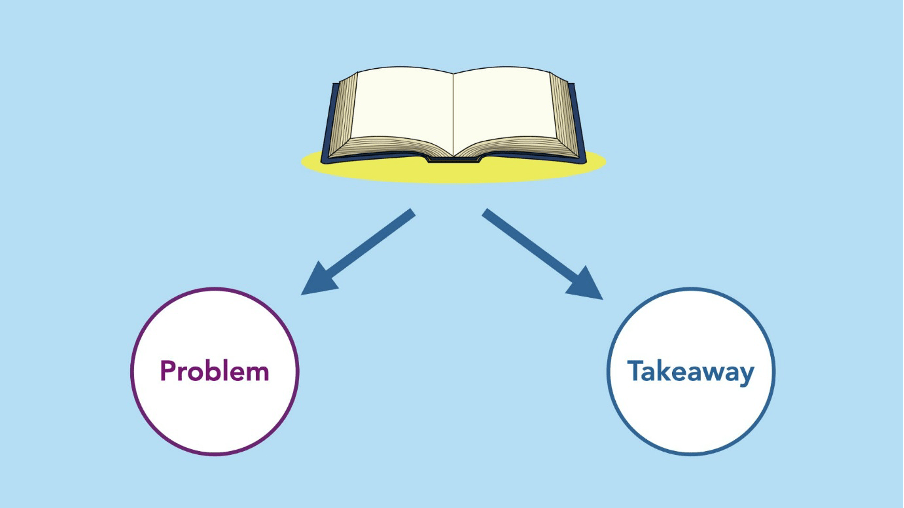

You’ve probably heard of a theme before. There’s definitions of it everywhere, but I find most of them to be jargon-filled and needlessly complex.

Here’s how I view a story’s theme:

A theme is a story’s problem and its takeaway.

That’s it. Super simple.

And as it turns out, a theme isn’t just reserved for the story-level. It also goes down to the idea-level as well. But to see it, you have to use the Thematic Lens to break your ideas down into problems and takeaways.

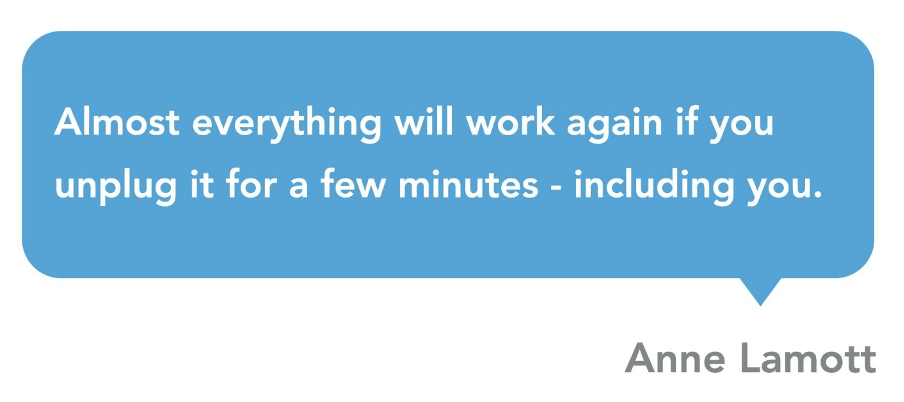

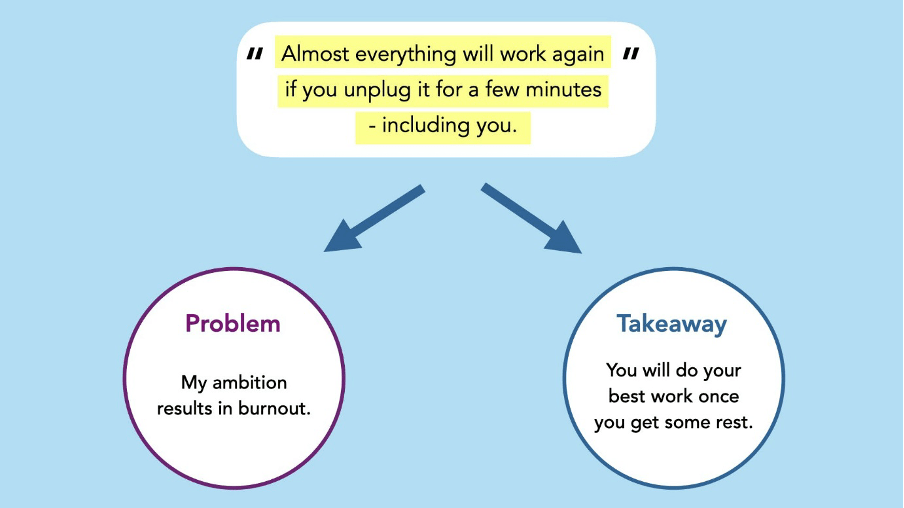

For example, let’s take a look at this quote by Anne Lamott:

What’s the theme that lives within this quote?

Well, if I break it down into a problem and a takeaway, it’ll look something like this:

Now that I have the problem and takeaway separated, I can see the beginning of a story start to unfold. Perhaps I’ll introduce an ambitious character that prioritizes getting stuff done, but is always teetering on the edge of burnout. Or I’ll look for a study where researchers tried to understand the link between ambition and burnout, and see if that’s something I can build a narrative around.

There are many paths this story could take, but it all started because I was able to find the theme that lived within a simple quote.

Pinpoint the problem and the takeaway you want to address in your story. That’s the starting point for everything. But once you do that, make sure you place a majority of your focus on just one of these two components.

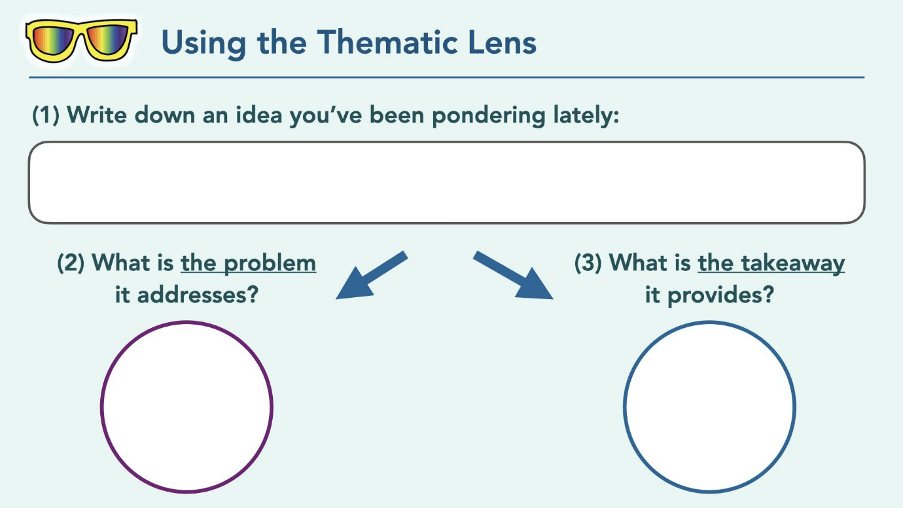

Okay, put it to practice.

The first step is to write down an idea you’ve been pondering lately. Earlier, we used someone’s direct quote, but this time, have it be something you learned or a reflection you’ve had recently. It could even be a piece of information that you jotted down in your notes the other day.

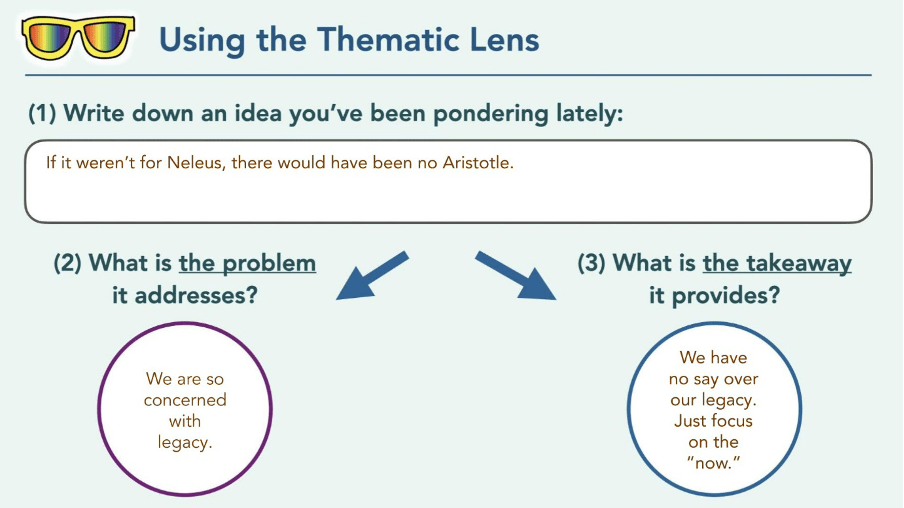

In my case, I recently learned that Aristotle’s writings were preserved by a man named Neleus, who history has long forgotten. But in reality, Neleus was super important because if it weren’t for him, we would’ve never known about Aristotle’s brilliance.

So I’ll write down the idea in the first box:

The next step is to find the theme that lives in the idea. In other words, you’ll separate it into a Problem and a Takeaway.

Take a minute or two to think through this, as it could be a bit tricky. To make it concrete, I’ll show you how I did it for the Aristotle / Neleus idea.

The immediate thing that strikes me about this idea is the problem of legacy. So many of us want to preserve a legacy, but the takeaway is that legacy is never in our hands. It’s other people that will determine whether your name lives on, so you should just focus on the present moment.

So here’s what I came up with for this idea’s theme:

Now I have a concrete problem to build a story around, and a takeaway that will deliver a soft landing. Keep in mind that you could have derived a whole other theme from that idea, and that’s perfectly fine. The Thematic Lens doesn’t yield any one correct answer; it all depends on the person using it.

All right! Take a few minutes to find the theme that lives in your idea, and note it.

Now that you’ve used the Thematic Lens, the next few lessons will show how you can make your theme come to life. But first, I need to address the biggest mistake that storytellers make when thinking about their problems and takeaways.

In our last lesson and practice, we went over the definition of a theme:

Once you have a problem and a takeaway, you have everything you need to start your story. But if there’s one thing I want you to remember, it’s this:

The biggest mistake storytellers make is that they focus too much on the takeaway. They rush to deliver the takeaway without the sufficient build-up required to make their audience care about it in the first place.

Consider these three takeaways:

Cool. There’s wisdom in these statements, but they fall flat. They sound like cliches and truisms that we all nod our heads in agreement about. It’s stuff we’ve heard before, and won’t really make an impact on how we think about the world.

Here’s the stark reality. If you just communicate a takeaway…

… No one will care.

So don’t focus too much on the takeaway.

Instead, focus on the problem.

Great storytelling is about presenting a struggle so that people relate to it or find it exciting to discuss. In the realm of philosophy, there’s a reason why the great questions of life are still being asked today. It’s because they’re not designed to have concrete answers that we’ve settled upon. These questions endure because we find different ways to ask them with each successive generation, as each cultural shift finds a new angle to address these old inquiries.

In Thinking In Stories, I go over the technique of Problem Framing in great detail. It’s such a crucial thing to understand, so we even do a 30-minute workshop exercise in real-time together.

When you’re absorbed in a story, why is that? When you can’t help but to turn the next page or to watch the next episode, what’s going on there?

It’s not because you want to hurry up and get to the ending. If that were the case, you could just read a plot summary of the story and know what happens right away.

It’s because you’re immersed in the tension of the narrative. You’re invested in the struggles that are being shown, and you want to understand how exactly they’ll be resolved over time.

In other words, you truly care about the problem of the story.

Earlier, we discussed the importance of the problem over the takeaway. Takeaways won’t resonate if the problem hasn’t been sufficiently communicated.

But how exactly do you get people to care about your problem?

Well, allow me to introduce the technique of Problem Framing:

One of your priorities as a storyteller is to frame the problem in different ways so people talk about it. By presenting your problem through various angles, you’re able to introduce a unique take on something that might otherwise be familiar.

To frame your problem well, there are three universal things you can target to get people to care. It doesn’t matter who the person is – these three elements pique interest irrespective of their background.

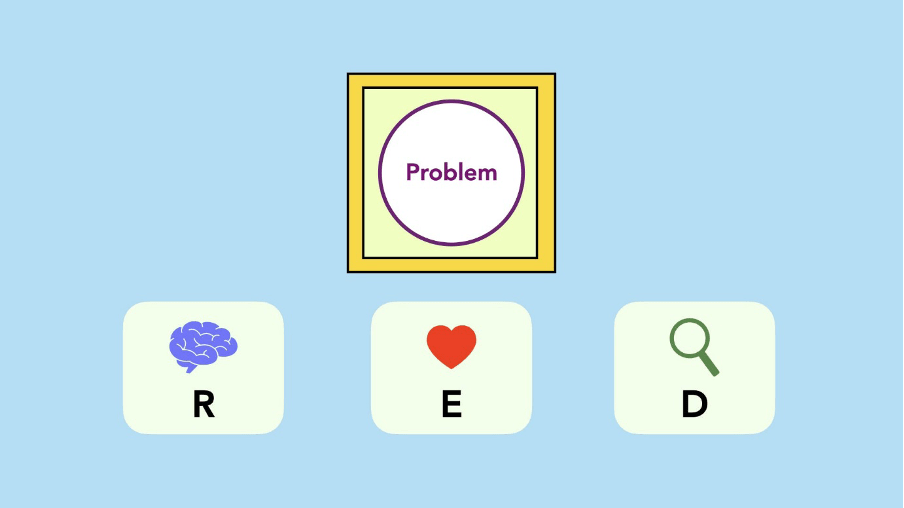

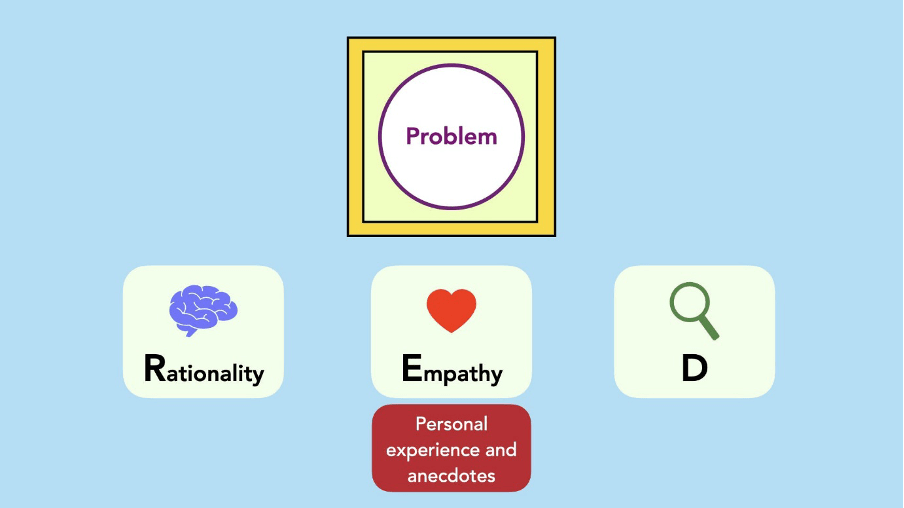

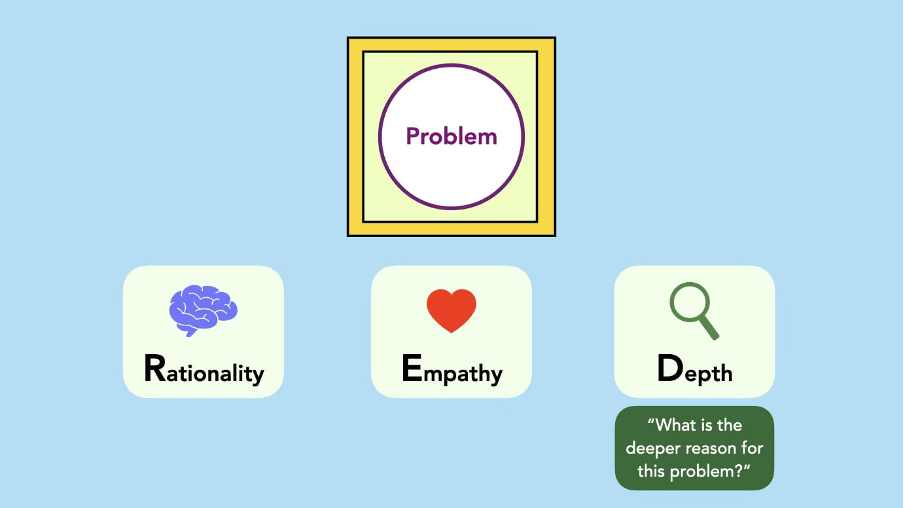

An easy way to remember them is through the RED framework:

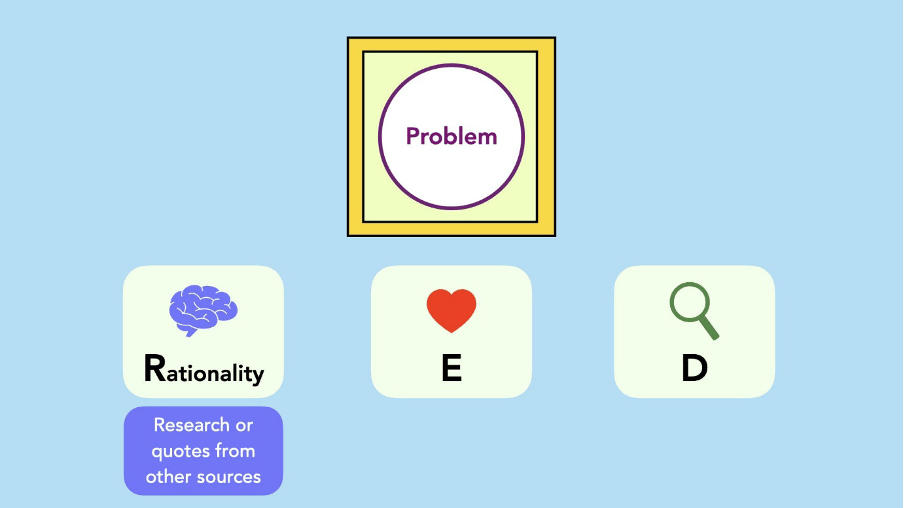

Let’s start with R, which stands for Rationality.

Everyone has a healthy dose of skepticism within them. Information usually passes through some filter, which needs to be siphoned and then accepted as something valuable.

By catering to someone’s Rationality, you are presenting your problem through the lens of reason. You want them to feel that it’s a valid and legitimate thing to be concerned about.

And the best way to to do this is to use external research or resources. By using an outside point of authority or a quote from an influential figure, you get the reader to care because of the strong nature of the source.

The next thing is E, which stands for Empathy.

Empathy is about developing a personal connection with the reader. And without a doubt, the best way to do this is to share a personal anecdote or experience.

By sharing a part of yourself, you make the problem much more relatable. While Rationality plays to the mind, Empathy plays to the heart. To open up an immediate connection, this is the best way to do it.

The last letter is D, or Depth.

This one is about generating an “A-Ha Moment” in your reader’s mind. It’s to get them thinking about the problem in a way they haven’t before. And the best way to do this is to ask one question:

“What is the deeper reason for this problem?”

This is the most important – yet also most difficult – part of your story you need to nail down. In Thinking In Stories, we use a helpful framework called the Depth Iceberg to do this. Then we put all these pieces together so that you have the concrete building blocks of your story.

But for purposes of this lesson, just ask yourself what the deeper reason is for your problem when it comes to Depth. Do it through different lenses, and put on your “philosopher” hat while doing it. What will this deeper reason ultimately reveal to your reader?

Use the RED framework when thinking through your stories. By playing to these three universal things, you’ll be able to frame your story (so people care).

Let’s kick off with this question:

When you open up an article and this is what you see, what do you feel?

This may be a personal preference thing, but when I see an article that’s nothing but long blocks of text, I get a little dismayed. It feels like it’s going to be a bit of a battle to get through it, and this is before I’ve even started reading the piece.

On the flip side, what if these blocks of texts were broken up with some visuals in between? Like illustrations, charts, or other diagrams?

For me, I’d be quite thrilled. I’d know that after digesting blocks of text, my mind would have a moment to process it with simple visuals. They’ll act as nice summaries or complements to what I just read, and they’ll guide me along the story in an enjoyable manner.

These visuals are what I refer to as Fun Magnets:

They help people feel engaged, especially if they know that a cool visual is coming up soon. It encourages them to stick with the story, to continue onward to see what’s right around the corner. I call them Fun Magnets because they draw you in immediately, even if you’re not quite sure what they’ll be about.

Fun Magnets are not limited to illustrations. They could be frameworks, graphs, spectrums, diagrams, the list goes on. Their primary role is to simplify complexity, and to act as visual ushers that keep the story moving along.

If you feel like your story could use a little shine, use a Fun Magnet. Create a graph that simplifies an insight. Draw a doodle that visualizes a point you just made. Not only does it liven up your story, it instantly gives you a unique style.

Fun Magnets are an underrated tool in nonfiction storytelling, so use them to your advantage.

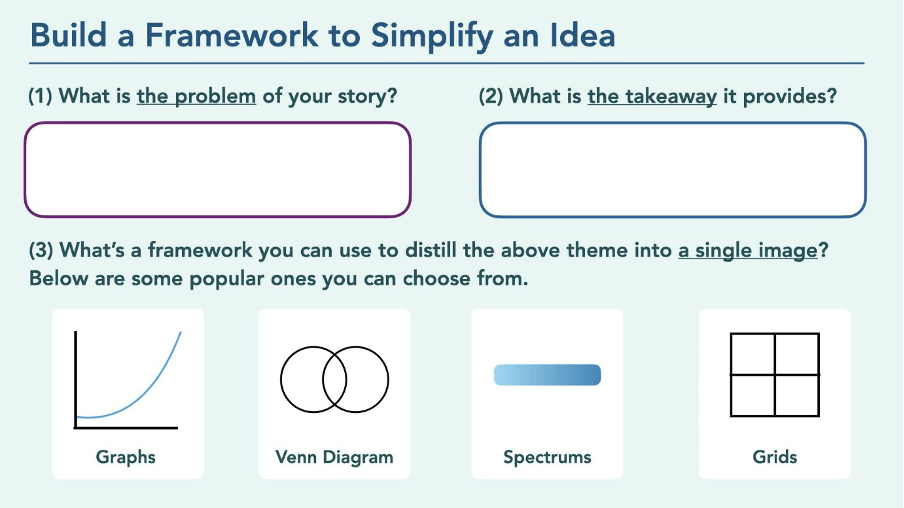

As always, we’re going to start with the theme.

Take a minute to enter a problem and a takeaway you want to build a story around. If you can’t think of one, use the ones you entered in for the Day 3 workshop (where you unearthed the themes living in a quote and an idea).

All right, great.

Now you’re going to build a visual framework using one of the examples I’ve included in the worksheet. You can either use a graph, a Venn diagram, a spectrum, or a grid. Draw it on your blank sheet of paper, and feel free to experiment with different types.

When thinking through the options, try to get a sense of which framework will suit your problem. For example, a Venn diagram will be great if you want to show how two different concepts can converge to deliver an insight. Or a spectrum can indicate the nuances that live between two extremes.

When I created my piece, Finding Peace Within the Pandemic, I wanted to show how the responses to the pandemic weren’t binary. It wasn’t just alarmists and optimists, but rather a gradient of positions that exist between the two poles, like so:

This is an example of a spectrum at work, but there are many others to choose from. To make things simple, choose from one of the four outlined on the worksheet, and draw it out on your blank sheet of paper.

That’s it! You’ve created a framework that has simplified the theme you want to communicate.

Let us now go over another way to share your idea, but using an unbelievably underrated tool. It’s one of my favorite topics, and I think you’ll find it useful.

The most effective tool in storytelling is worldbuilding. But here’s what’s incredible:

Most people never use it.

In fiction, worldbuilding is a given. Since everything is birthed from your imagination, you have to create a universe for your audience to play in.

With nonfiction, however, storytellers tend to ignore it. Perhaps it’s because they think that worldbuilding is a grandiose endeavor – something that results in Hogwarts or Mordor. Or maybe it’s because it’s not anchored in reality, which is where their ideas reside.

Regardless of the reason, there’s a huge blind spot here. And whenever you have a blind spot of this magnitude, an equally large opportunity awaits.

One of the great challenges in nonfiction is making your ideas easily communicable and fun. Philosophy is an apt example. If you pick up the work of any philosopher worth their weight, it can be an intellectual slog to sort through. Verbose statements, run-on sentences, and word salads are features, not bugs. There’s a lot of wisdom embedded in the text, but it’ll require in an inordinate amount of effort to extract it out.

A great storyteller takes that wisdom and builds a world around it to make it memorable.

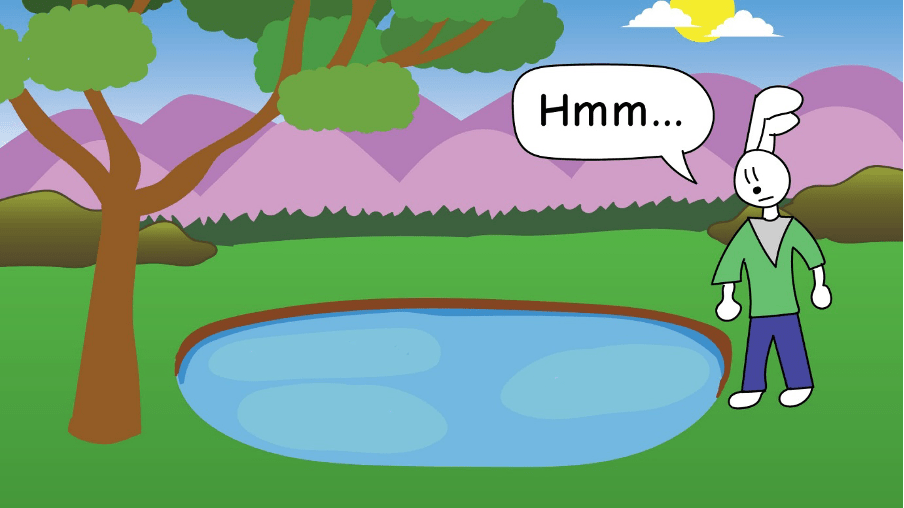

For example, the philosopher Peter Singer wanted to express why we have a moral obligation to help people in poverty. But rather than provide a lengthy dissertation on the subject, he asked his readers to enter a small world he built.

He asked people to imagine a little girl drowning in a shallow pond. You happen to be walking by in an expensive business suit, and encounter the girl as she’s screaming for help. You can easily save her by jumping into the pond, but of course, your beloved suit will be ruined. So with this in mind, you decide not to jump in and continue walking past her.

You would likely be repulsed by this. But Singer would argue that this is exactly what we’re doing when we don’t help impoverished people by giving what we can. He would say that giving away a portion of your income to help those in need would be a minor inconvenience for you, but a life-saving act for its recipients. And by not doing so, you are choosing your expensive suit over the little girl in the shallow pond.

Whether you agree with Singer or not, you can’t deny the power of this simple world he built. In fact, this small thought experiment changed the lives of many, and is responsible for many charitable causes that have developed ever since.

This is just one example of the power of worldbuilding, and is something I’ve learned throughout my years as a storyteller as well.

In Thinking In Stories, I go over a simple framework I use to introduce characters and build scenarios. It’s called the Three P’s, and after you learn it, you’ll be able to apply it to any idea of your choosing. I’ve used it time and time again, to great effect.

Worldbuilding is one of those secrets that most storytellers haven’t figured out yet. So if you’re feeling a little stuck, try stretching your imagination and add some fiction to your narrative.

That single technique can make your story stand out from the rest.

“Choose the shorter word.”

“Replace commas with periods.”

“Use the active voice.”

Whenever I see people give advice like this, I mentally shake my head (I wouldn’t do it physically because at this point, my head would just swivel off my neck because of how often I see it).

Sometimes I wonder if these people have ever read Dostoyevsky. Or James Baldwin. Or Jorge Luis Borges. Or Hannah Arendt. Or any writer that has mastered the craft.

If you read any of these brilliant people, you’ll see that they used plenty of commas, big words, and passive voices. They didn’t adhere to iron-clad writing rules to create their classics.

Their writing only followed one rule:

They did it with style.

An idea becomes a story when placed in the hands of someone with style. As Bukowski said, style is what transforms an everyday thought into something fresh and exciting.

In writing, this process is known as “finding your voice.” So how does one do that? Is there a concrete process you can use to do this?

Well, I have an analogy here that may help.

I used to teach high school students how to make beats (primarily hip hop). In our first lesson, I would ask them what their favorite beat was. Then I’d say, “Okay cool. We’re going to recreate that beat together.”

Instead of having them think of a melody or drum pattern from scratch, I started with a beat they already knew and loved. That way they didn’t have to wonder if their beat was going to be any good or not. Instead, they could just focus on learning the mechanics, and fill their toolkit so they could later use it for their own work.

The same sentiment applies to writing.

We are all influenced by other writers, as their success is what inspired us to try out the craft in the first place. So when you start out, take in those influences and use them as the starting point. Of course, don’t plagiarize them, but emulate their tone to get an idea of what might already be good. That way you don’t have to wonder whether there’s an audience for your tastes and preferences.

Once you do that, then you iterate. Continue working on stories, and reshape your tone based on your interests and experiences. Keep publishing, get feedback, and work on your next one. And if you don’t get feedback from the outside world, use your inner compass to get a sense of progress. This is where your intuition and persistence come into play. If you’re earnest with both, then it’s only inevitable that a style will develop.

That sense of style will morph and take shape over time, and it’ll be your greatest asset as a storyteller.

Remember, there are no iron-clad rules to writing.

Only iteration, evolution, and change.

For years, I knew I wanted to write something about money. Since it’s the greatest story humanity has ever subscribed to, it seemed fitting that I would create a story about it one day.

However, I had no idea where to start. With such a huge and daunting topic, where would I even begin? What can I possibly say that hasn’t been said already? Who am I to say anything on this topic anyway?

With these doubts in mind, I shelved the idea and told myself I’d get to it later. After all, there was no shortage of other topics for me to touch, and they were ones I felt more comfortable writing about.

But as time went on, I couldn’t ignore the idea’s presence.

As a creator, you know the feeling. There are certain ideas that refuse to depart the crevasses of your mind, and you know you have to do something about it. It’s simply not enough to let it reside there – you feel compelled to take action by imbuing it with your voice, and to share that result with others.

In other words, there’s a story within you that must be told.

Sometimes you wait for the right moment to begin. You wait for inspiration to strike, or for the proper mood to dawn upon you to start exploring.

The problem with this approach, however, is that you become reliant upon the whims of circumstance. Inspiration is fleeting, and moods even more so. As a storyteller, you can’t rely upon this kind of serendipity to craft your best work.

When I internalized this, my attitude toward the daunting topic of money began to shift. Rather than shelving it, I dusted it off and faced it directly. I journaled about money, I thought through my experiences with financial matters, and brought it up in conversation with people. I wanted to understand how money could enable a freedom that almost everyone desires, while also having the power to bring even the most rational people to their knees.

After weeks of thinking through this, it all came together one afternoon.

I was having a conversation with my sister-in-law, and I began communicating some threads of an initial framework. I told her that our relationship with money could be distilled into three main things: (1) Survival, (2) Freedom, and (3) Power. I imagined them to sit along a vertical spectrum, where you have to traverse through each one sequentially to experience how money influences your identity.

Immediately afterward, I did a super quick sketch to ensure I wouldn’t forget its structure:

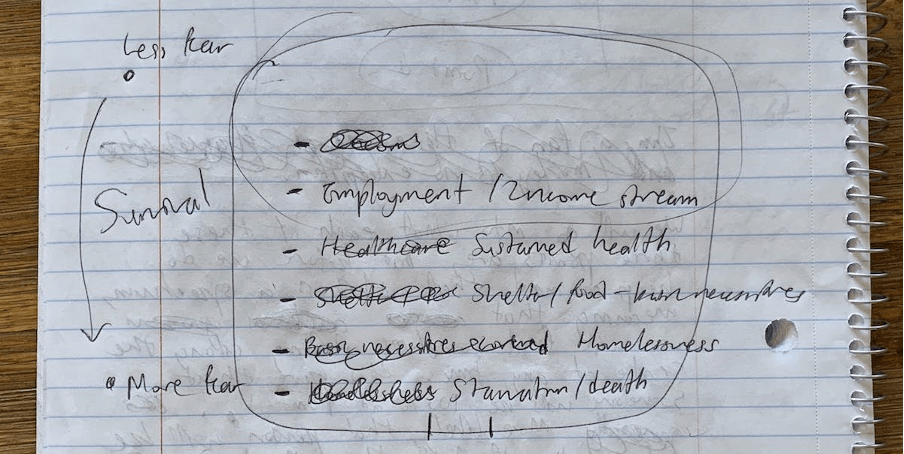

Then I started breaking down the Survival phase into smaller sub-phases, showing how each one leads to either an increase or decrease in fear:

That was all it took for me to get started. The initial seed was planted, and now it was time to grow it into a story.

For the next few weeks, I used the Thinking In Stories method to take this idea and transform it into a cohesive narrative. I used a personal story about my fear of homelessness to articulate how money distorts our sense of survival (a technique I call “problem framing”). I distilled our relationship with money into a single diagram called the Money Spectrum (the method of “simplifying complexity”). I built a world where I took my audience in a step-like fashion through each stage, having them feel either the haziness and clarity that accompanied each area.

By the time I was finished, I had a 7,500-word, 50-illustration post on my hands. I titled it Money Is the Megaphone of Identity, and published it on the site in February 2020.

The post was a hit. A huge hit.

Prior to this post, I never considered myself to be a finance or business writer. After all, my main interests were (and still are) philosophy and psychology, so the realm of money seemed well outside my wheelhouse.

But upon publishing this post, I realized how a well-crafted story can make you a legitimate storyteller in any field you choose. It doesn’t matter whether you’re a novice or an expert in that field; if your story is great, then that alone is enough.

Morgan Housel, my favorite business writer alive today (and perhaps yours too), DM’ed me the next day telling me that he enjoyed the piece. He even shared it in the Collaborative Fund newsletter that week.

Nick Maggiulli, another one of my favorites, named it as one of the best pieces of investment writing in 2020.

Ali Abdaal, one of my favorite YouTubers, has shared and read it multiple times.

With a single story, people were now interested in what I had to say about money. By organizing a few strands of thought into a cohesive narrative, that provided a credibility that otherwise would have taken years to build.

Perhaps you’re in that same position I described earlier. Where you have a big idea you want to elaborate on, but are unsure of how to approach it. You know there’s a story you need to work on, but you want a practical toolkit that will help guide you through the process.

Thinking In Stories is that toolkit in action, and it’s the exact method I used to craft my big money post. To create a story that can’t be ignored, the tools appear to be quite simple in theory:

- Articulate the problem clearly

- Simplify your ideas into something digestible

- Build a world to make it fun

- Create frameworks that stick

- Structure your ideas into a compelling arc

But what’s difficult is in knowing how to apply these tools. It’s one thing to know how to use a chainsaw; it’s a whole other thing to actually put it to use. That gap between knowledge and application is what I want to bridge, and I’ve made it a personal goal to do that for the art of storytelling.

If there’s one thing I want you to remember, it’s this: A great story establishes credibility that would have taken years to build. It would have taken me decades of climbing the corporate ladder to draw the attention of the kind of people that my money post did. But by transforming a simple framework into a compelling narrative, that story quickly did all the climbing for me.

That’s the power of storytelling. And if you want to understand how to do it in a fun and repeatable way, then Thinking In Stories is here to show you how.

One thing you may have noticed is that there’s no mention of the “classic” methods you may be familiar with. No Hero’s Journey. No 3-Act structures. No hook/build/payoff. While these techniques are useful, I don’t use them for a reason.

The problem I see with a lot of storytelling advice is that it doesn’t take into account the individual’s preferences. It assumes that you should use the Hero’s Journey to structure your story, regardless of where you draw your inspiration from. Does it make sense to use a 3-act structure for something that is research-driven vs. one that’s entirely fictionalized? What does it mean to have a payoff in your story when you’re not dramatizing anything?

Before you try out any strategies or techniques, you have to first answer this big question:

Everything starts there. What tone are you most comfortable with? How do you naturally package your ideas? Where do you draw your inspiration from?

You must first start with identity before moving on to any of the techniques. Only then are you aware of what feels natural, what feels experimental, and what will ultimately feel authentic. And it’s that last part – authenticity – that will be the gateway to developing a style.

The Thinking In Stories method starts with identity, and uses that as an anchor for the whole course. By doing so, you’ll know which frameworks and techniques are natural fits for your storytelling DNA, and which ones are asking you to stretch your imagination. It’s this marriage of an innate and experimental mindset that makes this method so powerful.

Thinking In Stories was designed to help you figure out who you are as a storyteller. Then it’ll give you all the tools you need to actualize that identity and bring resonance to your ideas.

You must be logged in to post a comment.